New software is making it possible to plan, simulate and optimize a production layout in three dimensions – in a digital playground.

Anyone who has ever planned or redesigned a factory knows how demanding and complicated it is. Whether the planners are starting from scratch, that is, virtually on a greenfield site, or modifying an existing plant layout, it is no small task.

The planning was once carried out with paper and pencil, and later on a digital drawing board with CAD technology. For years, Freudenberg Sealing Technologies (FST) has used a method known as the Production Preparation Process (3P) from its lean toolkit. The team simulates the future production process with the help of cardboard boxes, paper layouts and no shortage of thought and analysis.

More and more, FST is starting to use digitalization for its layout planning. Even complex production lines and automated robot cells can be planned and simulated using visualization software from Visual Components, a unit of KUKA. All the work steps involved in the process are depicted realistically in a 3D environment. Mike Anttila, CTO of Visual Components, even talks about “3D playgrounds for the industry.” This means everything intended for a real-life shopfloor is depicted virtually in advance – including realistic operations showing the worker’s path or the potential integration of a robot.

Automation is on the rise in manufacturing, as is the total number of robots or cobots giving their human coworkers a hand. This all makes future production processes increasingly complex. If these multilayered systems can be simulated, the planners will know in advance whether or not the processes will work. That knowledge can save the company time and money.

Digital Simulation

Similar to 3P, processes and workflows can be optimized even before a new or restructured production system starts up, and robots can be “trained” for later tasks. By exploring future processes in theory, it becomes possible to test variations in advance. Sometimes it turns out that equipment envisioned for the work would not function as intended. Had it already been ordered, it would later have to be modified at great expense.

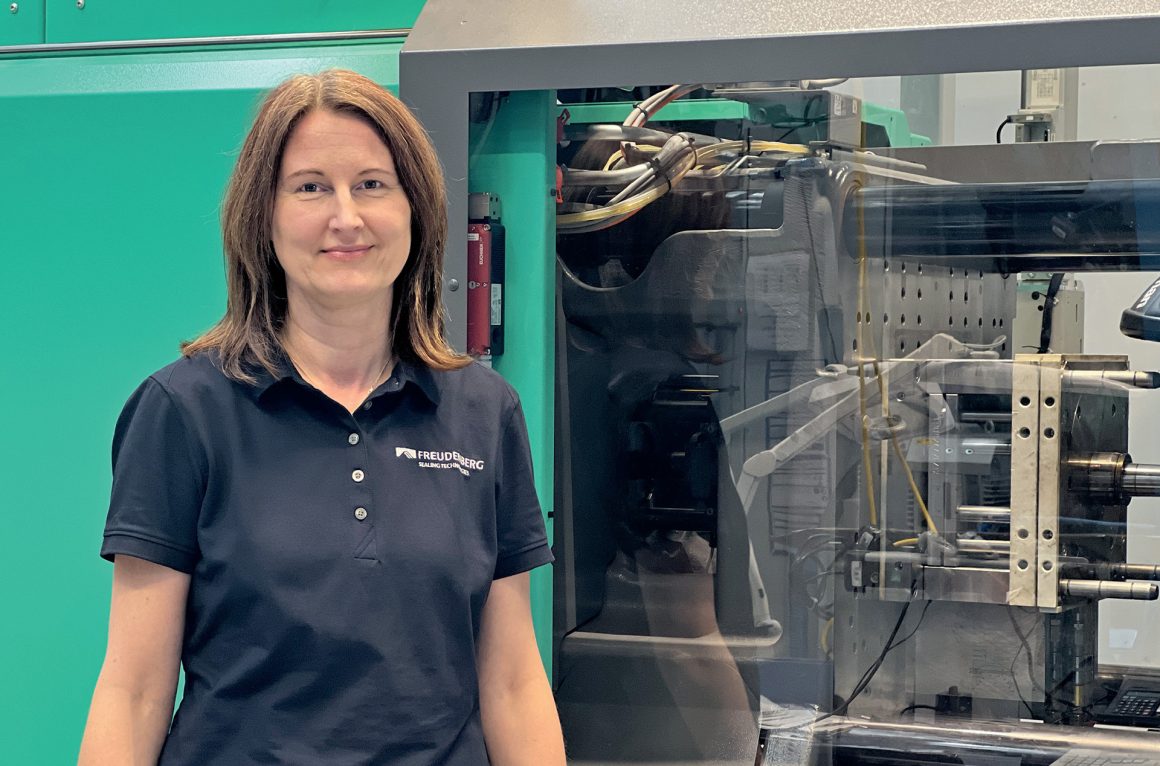

“In June, FST acquired two global software licenses from Visual Components, and we have now trained the first employees and implemented the software,” said Alexandra Krupp, Director, Global Process Development, Technology & Innovation. An early project with the new software is slowly taking shape. For example, the Lead Center Fluid Power in Schwalmstadt is planning to automate a cell where each press is directly linked to a small post-curing oven.

“The Lead Center would like to move away from post-curing and block manufacturing and produce by single-piece flow instead,” she said. That means every piece moves out of the press right into a connected oven, instead of being collected on plates and post-cured as a block in a large oven. The plan also calls for automated mobile robots (AMRs) to carry away finished parts in a dedicated lane, reducing the amount of walking for operators. The AMRs can also be trained by using the software. Another pilot project is planned and will be launched shortly.

“During the next stage, we will be feeding our own step data into the system,” Krupp added. For example, existing presses, equipment, ovens and phosphating systems with their original dimensions are stored in an electronic catalog, and new systems and their specifications are added. They can be easily moved into the virtual layout with a drag-and-drop tool, and rearranged and shifted at will – until everything fits and can be executed.

Visual Components

This Finnish company specializes in 3D simulation for factory planning. It was founded in 1999 and acquired by the KUKA Group in 2017.

Augsburg-based KUKA AG has been majority-owned by Midea, a Chinese company, since 2016. KUKA is one of the leading providers of industrial robots in the global market.

FST is a supplier to KUKA while simultaneously using the company’s robotic systems.